Negligence or Acceptable Risk? The New Standard of Clinical Harm

Where should the line be when doctors are over-worked but patients bear the consequences…

Despite the best of intentions, no doctor makes it through an entire career without causing harm. Indeed, sometimes they may intentionally inflict harm in the pursuit of a greater good. A child screaming in discomfort in the dentist’s chair as the lidocaine is injected is certainly experiencing a significant amount of harm, yet the parents and dentist acknowledge that some degree of harm is necessary to bring about a greater good. We can create endless similar examples, such as the greater good that comes from your three failed cannula attempts.

There is a different form of harm, however, that we must discuss: the harm we do not intend to inflict. Iatrogenic harm refers to harm experienced by patients that results from medical care. This is different to negligence, which can be considered as a failure to use reasonable care or acceptable standards of practice.

Therefore, we can say that all harm resulting from negligence is iatrogenic, but not all iatrogenic harm is negligent. So, how do we decide on where the line is between the two?

If we try to understand negligence, we will come to see that it is about expectation. It is about what a competent doctor could have reasonably foreseen or prevented. Reasonable care once felt fairly tidy and understandable, but in modern medicine, guidelines multiply faster than we can read them, and the rate of published papers climbs out of control.

So what is reasonable then? Try it yourself. Is it reasonable to have missed sepsis when a doctor is covering four wards overnight? Is it reasonable to rush the consent conversation for a patient receiving a laparotomy in the evening, as you have a clinic to attend?

We still wrongly believe that all medical harm is purely biological (i.e. prescribing the wrong medication for a patient’s care) when, in reality, it is often informational, such as patients being overwhelmed or misled by excessive information, or structural, such as harm arising when a patient is not followed up and becomes lost in the system. These forms of harm are very difficult to measure, so they often escape attention.

Perhaps negligence needs to be reimagined for a healthcare system that seems to be running at 110%. Consider all those legal tests that you will have learned in medical school (Bolam, Bolitho and the like), they imagine a clinician who is time-rich and has continuity over their patients. It is arguable whether modern clinicians have any of these, but we are judged as if we do.

Weekly Prescription

The Compensating Consultant: Alfred Adler on The Ward

The Austrian doctor and psychotherapist Alfred Adler, perhaps unknowingly, unravelled the inner workings of many NHS doctors when he described the theory of Compensation. He noted that compensation is the human drive to counter feelings of inferiority by striving for mastery. You take one negative feeling and counter it by overdeveloping other traits.

Many of us will be relating this archetype to a specific hospital consultant. When that CCT is placed in your back pocket and you are given a consultant post, there is an implicit belief that you should just know, lead, and contain risk. All these expectations invite overcompensation through working longer or taking on excessive responsibility.

How interesting. If this theory is true, we have a telltale method of examining an NHS trust and identifying who is compensating and who is not. But this seems to be the issue. Testing the theory has proved to be fairly difficult.

Karl Popper (the fella behind the scientific method) had one large issue with the theories of social psychologists such as Adler and Freud. He highlighted his objections in Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. His main critique was that we should hesitate to take theories such as these seriously, and certainly pause before labelling them scientific, because they are unfalsifiable in nature. Put simply, it is incredibly difficult to disprove them.

So while it may lack robust empirical support, it makes intuitive sense that compensation is a form of medical adaptation. It is a form of adaptation that can very easily become identity.

Retire & Rehire

Best of both worlds or exploiting a loophole?

Some of our consultant colleagues find themselves at a crossroads late in their careers as they weigh the desire for retirement against the pull of continuing clinical practice — perhaps just to keep themselves occupied, top up their income, or to share their experience with the next generation.

Traditionally, retirement was an all-or-nothing event where you stopped work, claimed your pension, and left the NHS. But in recent years, a new approach has become more common. You may have noticed the occasional consultant retiring and almost instantly returning to the department. This retire and rejoin or twenty-four-hour retirement route is an alternative that an increasing number of people are considering.

It allows a consultant to formally retire, access their NHS pension, and then continue to work while also accruing pension benefits. It is certainly an attractive option that combines financial security with continued professional contribution. The psychological side of retirement after decades of working as an NHS consultant is not often spoken about. There is a loss of professional identity, purpose, and routine that comes with saying goodbye to the role that has defined the majority of your adult life.

Retire and Return Mechanics

The way it works is that a consultant must resign from all NHS posts and formally retire, taking at least a twenty-four-hour break before returning. Once re-employed, there is no automatic restriction on the number of hours you can work.

It sounds appealing, but the biggest hurdle for the consultant is that the retire and rejoin route is constrained by employer discretion. Trusts retain the authority to determine whether they will allow a returning consultant, the number of sessions offered, and the terms of the contract. Some trusts are reluctant to support the practice at all, while others restrict it to shortage areas or critical specialities. There will also be stories of trusts not allowing this practice for consultants they have had long-standing difficulties with.

One argument that often resonates with NHS trusts is that employing a retired consultant under the scheme may reduce the trust’s contribution to the NHS Pension Scheme while still retaining experienced clinical capacity in areas of need. This is the case because under the NHS Pension Scheme, an NHS employer must pay an employer contribution rate on pensionable pay, which is around 23.7%. Pensionable pay, therefore, drives how much the employer contributes. The lower the pay or the fewer the sessions, the lower the employer contribution cost.

If a consultant formally retires, claims their pension, and then returns on a new contract, a trust may negotiate reduced working hours or reduced pensionable pay. This is not automatic. It depends on the contract the doctor agrees to for their re-employment, including their hours, session count, and pensionable pay level.

Board Round

A round-up of what’s on doctors’ minds

“Wonder if this year, anyone will be able to beat the three brave souls who submitted 16 unique speciality training applications in the 2024/25 cycle.”

“Spent 10 minutes explaining to my consultant that the next patient is hard to communicate with, often slurs words and makes unusual noises whilst talking. So of course, the moment the ward round reached his bed number, he began speaking clearer English than me. It’s been a long week”

“Is this an implicit bias, or are the radiology reports from external teleradiology companies always less optimal and accurate than the ones reported in-house?”

“A radiology classic: Always struggled with the thinking that suggests a patient with 7,215 previous CT Heads warrants another CT head for ?confusion”

Referrals

Some things to review when you’re off the ward…

In 2024, the NHS spent £216 million outsourcing reporting to private teleradiology services. This is a 24% rise from 2023 and is nearly double the levels seen pre-pandemic.

The chief executive of the NHS, Sir James Mackey, recently proclaimed that there are indicators suggesting that fewer resident doctors are striking than in any of the previous 12 rounds of industrial action. Some doctors have been quick to note that some of the polling has relied on notably small sample sizes, comprised of only 50% BMA members. So for now, we can only speculate how Sir Mackey arrived at his conclusion.

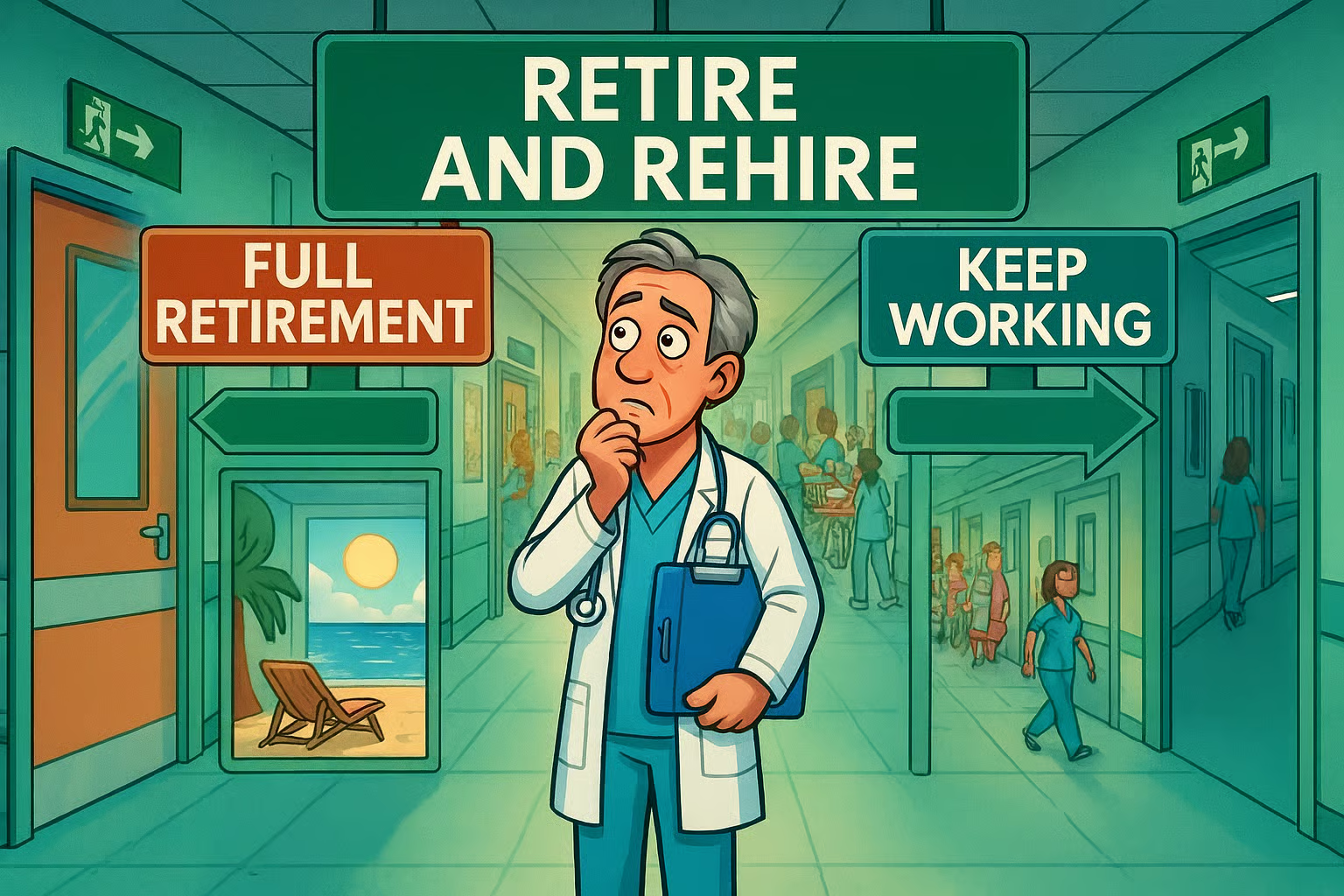

Weekly Poll

Are you participating in the current round of industrial action?

…and whilst you’re here, can we please take a quick history from you?

STAT Note

The Case of Bed 14 (again)

“Matteo, bed 14’s aunt is here at the bedside, she says she would appreciate an update from the doctor”

Bed 14? Again? You think to yourself, you’ve already updated three members of his family on three separate occasions in the past 48 hours. Each wants to understand and to be reassured directly by you.

You turn to complain to the ward clerk, but before you can finish the rant, he jumps in. “Matteo, there are real people out there who won’t be reassured by anyone else but you. Your words carry such significance and importance to them that their mere utterance puts them at ease. That’s a privilege not many have in society, mate.”

Silence fills the room for a moment as you acknowledge the well-made point. Has it made your job list any shorter? No, but has it momentarily changed your perspective? Perhaps.

Because behind the fatigue and the endless jobs list sits something we rarely acknowledge: the symbolic weight of our presence. It’s crazy how this truth often manages to evade us, to become a cliché. You aren’t just another person on the ward to the average family.

Having said all that, maybe try telling Bed 14’s family to try communicating with one another…

Share the News. Build the Community.

Help us build a community for doctors like you. Subscribe & Share On-Call News with a friend or colleague!

*We’ve done our best to keep this information accurate, but person specifications can change. Always check the latest person specification for your training programme before relying on this information.

Disclaimer:

Content in the On Call Newsletter reflects the personal views of individual authors and does not represent the views, policies or guidance of Medset Ltd. Articles are for general information only and do not constitute clinical or professional advice. Medset Ltd accepts no liability for decisions made based on this content.